Our work explores the ecological and evolutionary factors that determine infectious disease dynamics in reservoir hosts and cross-species transmission. We apply approaches such as spatiotemporal field studies of bats and songbirds, meta-analyses, epidemiological models, and machine learning to better understand how zoonotic pathogens spread within and between populations and species and how environmental change will alter infection risks. Specific themes we address include how land conversion (e.g., anthropogenic resources, urban habitats) affects infectious disease in mobile hosts, the evolutionary factors that shape reservoir competence and pathogen sharing, and macroecology approaches to host immune defense (e.g., spatial and species variation).

Much of our work is grounded in the diverse Neotropical bat communities of Belize and Panama alongside local work in Oklahoma and Texas on migratory bats and songbirds. We also embrace entirely computational approaches, including theoretical models and large-scale syntheses projects using public data.

Much of our work is grounded in the diverse Neotropical bat communities of Belize and Panama alongside local work in Oklahoma and Texas on migratory bats and songbirds. We also embrace entirely computational approaches, including theoretical models and large-scale syntheses projects using public data.

anthropogenic resources and infection

Although land conversion has clear associations with pathogen spillover, the mechanisms by which such changes shape host–pathogen associations remain unclear. Agriculture and urbanization provision many wildlife with anthropogenic resources and provide a gradient of environmental variation. Predicting how these resource shifts alter infection is challenging, as increased food abundance and availability can alter multiple and opposing ecological processes (e.g., elevated contact but improved resistance). We have developed a variety of theoretical models to explore how anthropogenic resources affect disease dynamics within and between host populations, while we use meta-analyses to synthesize results across studies and test model assumptions. Much of our work has confronted these findings through studies of vampire bats in Latin America, where this blood-feeding host species capitalizes on abundant anthropogenic food provided through livestock. Prior studies have examined how gradients of livestock abundance shape vampire bat immunity and outcomes of pathogens such as Bartonella, hemoplasmas, and rabies virus. Ongoing work uses an extensive and long-term mark–recapture study in Belize alongside stable isotope analyses and metagenomics to explore how individual- and population-level dietary shifts shape host immunity and infection risks. However, similar ideas could be applied to other Neotropical bats (e.g., frugivores and nectarivores) or to North American songbirds within urban habitats.

urban residency and epidemiology

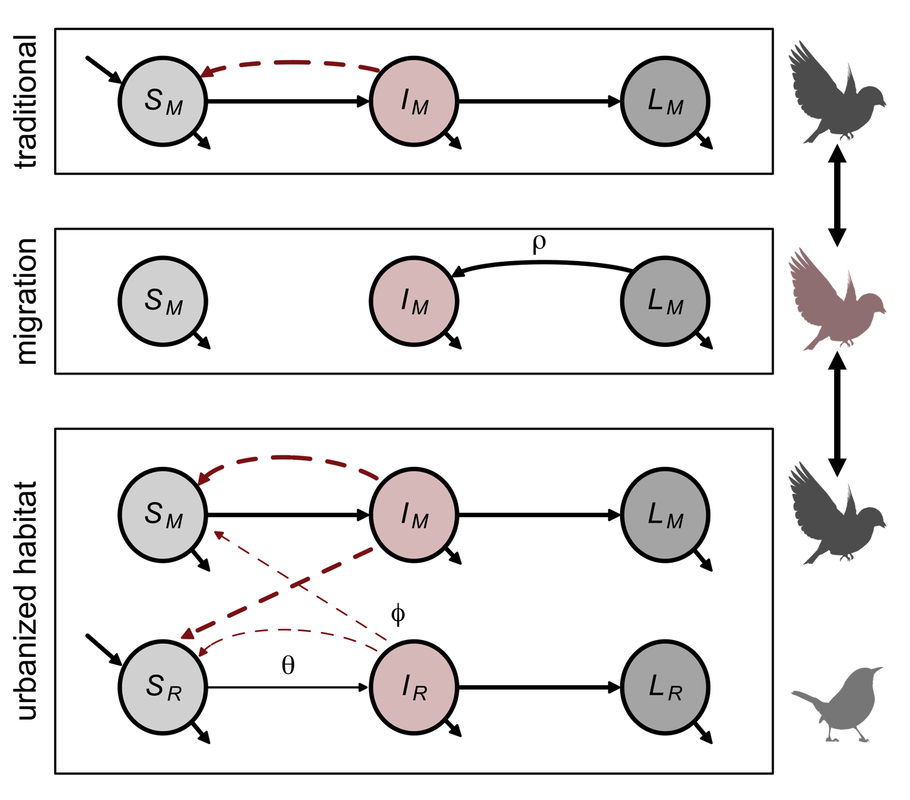

Land conversion affects not only local infection dynamics but also long-distance movement between habitats. Many migratory species are increasingly overwintering (or entirely abandoning) migration in urban and agricultural habitats. These transitions could remove ecological mechanisms that reduce pathogen transmission (e.g., migratory culling), but adoption of sedentary behavior in urban habitats could benefit within-host traits like resistance. Recent work has begun to examine how urban residency shapes immunity for typically migratory species, and we are building general theory for how urban residency could affect disease dynamics when sedentary hosts interact with seasonal migrants. Of particular interest is how urban residency could shape the infection dynamics of pathogens that show cycles of latency and reactivation (e.g., Borrelia burgdorferi, flaviviruses, haemosporidians) for migratory songbirds and bats, and ongoing work aims to broadly identify the contexts under which animal migration will lead to pathogen relapse. We are addressing these questions by integrating theory and spatiotemporal field studies of migratory hosts such as juncos, thrushes, North American bats, and flying foxes.

competence and cross-species transmission

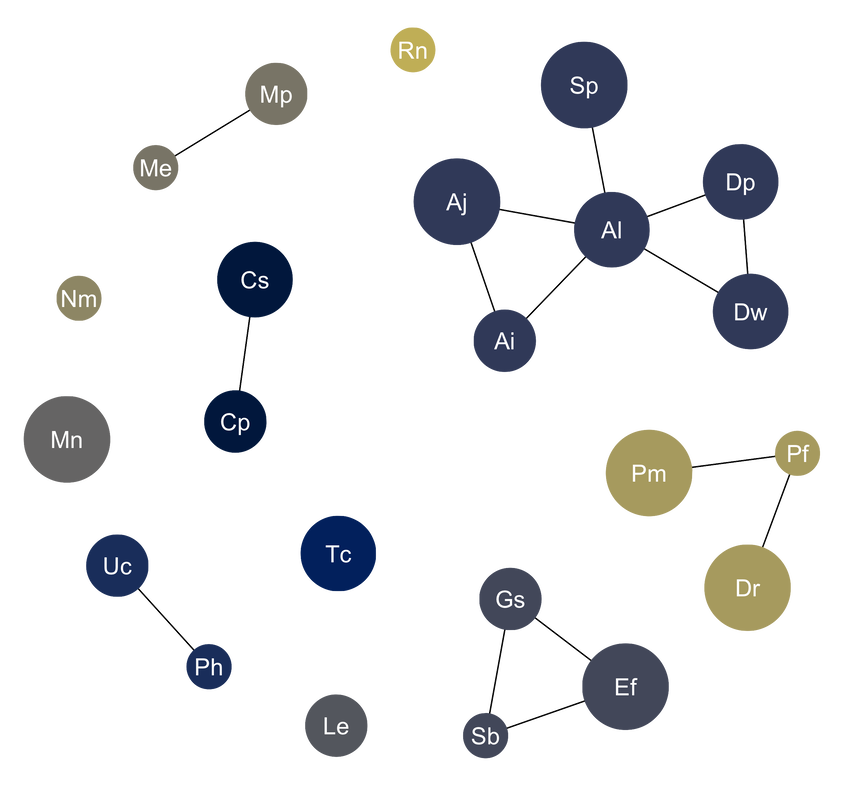

Many efforts to predict novel reservoirs for zoonotic pathogens rely on coarse information about the infection status of species rather than their ability to transmit pathogens to new hosts or arthropod vectors (i.e., competence), and such efforts are often biased towards viral pathogens. To best integrate predictive approaches into wildlife surveillance, we are combining pathogen discovery with machine learning and network approaches to identify the ecological and evolutionary drivers of reservoir competence and pathogen sharing. In our Belize bat system, we are using metagenomic screening and pathogen sequencing to reconstruct cross-species transmission, assess the relative contribution of host phylogenetic distance and ecological overlap, and understand whether host traits or clades show consistent changes in pathogen diversity with habitat fragmentation. From another perspective, we are using phylogenetic analyses and machine learning to characterize competence for Borrelia burgdorferi and other tick-borne pathogens across bird species. Ongoing work will test model predictions with surveillance of likely competent bird species across their annual cycle in Oklahoma and the broader region. We are also members of the VERENA Consortium, a collaboration among ecologists, virologists, and data scientists to advance zoonotic virus predictions. Continuing work is using machine learning to identify trait profiles of competent hosts and predict likely reservoirs for betacoronaviruses and hantaviruses, and various opportunities exist to test model predictions via immunology and pathogen screening in collaboration with field teams and museum collections.

macroecology of host immune defense

Much work on large-scale patterns in infectious disease are inherently biased by sampling effort and which pathogens are prioritized for surveillance. While sequencing efforts are increasingly providing more comprehensive characterizations of pathogen diversity, quantifying how immunity (e.g., susceptibility) varies across larger biological scales could provide more general predictions into what kinds of species in what kinds of environments are most prone to act as sources of emerging zoonoses or suffer population-level impacts of novel pathogens. At the species level, bats host many viral zoonoses without showing pathology, which could stem from distinct immune systems that co-evolved with flight. We are particularly interested in combining classic ecoimmunology and RNA-Seq to compare immune phenotypes between ecologically similar bats and birds to assess the contribution of flight versus evolutionary history. At the environmental level, populations can vary markedly in their immune phenotypes, but identifying the primary habitat determinants of host defense requires extensive spatial sampling. We have outlined general recommendations and future directions of "macroimmunology" research and have ongoing projects to differentiate competing spatial drivers of immune defense with an external global network of house sparrow sampling efforts. Similarly, future work will characterize immune differences among insectivorous bat and songbird populations across environmental gradients through Oklahoma. This is in tandem with other above projects that necessitate integrating immunological methods. For example, understanding relationships between urbanization, migration, and infectious disease requires identifying how immunity varies across both the annual cycle and across urban–rural site gradients, and statistical models of competence are likely to be improved by integrating immunological data (e.g., white blood cell concentrations, receptor binding).